SIR JAMES CLARK ROSS (1800-1862)

Sir James Clark Ross was a British naval officer who carried out important magnetic surveys in the Arctic and Antarctic and who discovered the Ross Sea and the Victoria Land region of Antarctica.

Sir James Clark Ross was a British naval officer who carried out important magnetic surveys in the Arctic and Antarctic and who discovered the Ross Sea and the Victoria Land region of Antarctica.

Early Life and Arctic Voyages

Ross joined the navy at age 11 under the tutelage of his uncle Sir John Ross. He made his first voyage to the Arctic in 1818 on an expedition in search of the Northwest Passage, followed by four Arctic expeditions under Sir William Parry between 1819 and 1827. In 1829-1833 he again served under his uncle in the Arctic. During this trip they located the position of the North Magnetic Pole on June 1, 1831 on the Boothia Peninsula in northern Canada.

By 1836, Ross had spent eight winters and 15 navigation seasons in the Arctic regions, an unequalled record. He was also a leading expert on terrestrial magnetism, having conducted the first systematic magnetic survey of the British Isles. His experience in ice-filled seas and his knowledge of terrestrial magnetism made him the logical choice for commander of an Antarctic expedition to study terrestrial magnetism in extreme southern latitudes; the voyage was strongly supported by the British Association for the Advancement of Science and the Royal Society of London.

A Voyage of Discovery – In Search of the South Magnetic Pole

The expedition set sail on October 5, 1839, with Ross in command of the Erebus and second-in-command Francis Crozier aboard the Terror. During the first summer they established fixed magnetic observatories at St. Helena and the Cape of Good Hope and spent two months taking observations at the Isles Kerguelen, before heading to Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania) for the winter. There they built another magnetic observatory, with the help of 200 convicts brought in by the Lieutenant Governor of Tasmania, Sir John Franklin.

While in Hobart, Ross learned of the discoveries made that past summer, by French and American expeditions also searching for the south magnetic pole. Ross was upset that both Dumont d’Urville and Charles Wilkes had explored the very area where he had planned to penetrate southward. Wilkes left Ross nautical charts showing his route and discoveries; however Ross chose not to follow in Wilkes’ footsteps. He wrote,

‘England had ever led the way of discovery in the southern as well as in the northern regions, I considered it would have been inconsistent with the pre-eminence she has ever maintained, if we were to follow in the footsteps of the expedition of any other nation. I therefore resolved at once to avoid all interference with their discoveries, and selected a much more easterly meridian (170° E.), on which to endeavour to penetrate to the southward, and if possible reach the magnetic pole.’

Furthest South and Discoveries in the Ross Sea

Furthest South and Discoveries in the Ross Sea

Sailing south from Tasmania, Clark encountered pack ice on January 5, 1841. The expedition’s next move was memorialized seventy years later by Roald Amundsen, ‘…these men sailed right into the heat of the pack, which all previous polar explorers had regarded as certain death…These men were heros – heros in the highest sense of the word.’ The ships pressed through the ice for four days before sailing into open sea again and Ross wrote, ‘We now shaped our course directly for the Magnetic Pole, steering as nearly south by compass as the wind admitted.’

Two days later, mountainous land lay across their path. Ross named the point Cape Adare and the region Victoria Land after the reigning queen of England.

The magnetic pole was predicted at the time to be southwest of the sighted land. Given that Wilkes had reported land to the west, Ross chose to sail east of Cape Adare and south along the coast where he hoped to find a way around to the magnetic pole. Instead, he sailed into a the region now named the Ross Sea and for two weeks, took soundings and tracked the coast of Victoria Land, naming the peaks of the Admiralty Range, the Royal Society Range, and various islands and geographic sites.

By January 22, the expedition surpassed James Weddell’s farthest south record and on January 28, they discovered Ross Island, naming its two volcanoes Mount Erebus and Mount Terror after the expedition’s ships. At the base of Mount Erebus, McMurdo Sound was named after an officer of the Terror. The discovery was described by the ship’s doctor.

‘We were startled by the most unexpected discovery in this vast region of glaciation, of a stupendous volcanic mountain in a high state of activity…my attention was arrested by what appeared at the moment to be a fine snow drift, driving from the summit of a lofty crater-shaped peak…As we made a nearer approach, however, this apparent snow drift resolved itself into a dense column of black smoke, intermingled with flashes of red flame emerging from a magnificent volcanic vent, so near the South Pole, and in the very center of a mighty mountain range encased in eternal ice and snow.’

On the same day, the expedition came to a vast cliff of ice, rising 50 to 200 feet above the water and extending for as far of the eye could see. They named it the Great Victoria Barrier and it was known as ‘The Great Ice Barrier’ for several generations, until it acquired its present name, the Ross Ice Shelf. The expedition sailed east along the ice cliffs for several hundred miles, but with winter approaching and no end to the barrier in sight, they turned back west in a last effort to find a route to the south magnetic pole.

On the same day, the expedition came to a vast cliff of ice, rising 50 to 200 feet above the water and extending for as far of the eye could see. They named it the Great Victoria Barrier and it was known as ‘The Great Ice Barrier’ for several generations, until it acquired its present name, the Ross Ice Shelf. The expedition sailed east along the ice cliffs for several hundred miles, but with winter approaching and no end to the barrier in sight, they turned back west in a last effort to find a route to the south magnetic pole.

Ross determined the location of the magnetic pole to be significantly farther south than previously predicted (76°S rather than 66°S at 146°E) and the route was blocked by impassable ice. They estimated the pole to be 160 miles (260 km) inland and reachable by sledge (the means by which Ross had reached the north magnetic pole), if they could find a safe site to overwinter. No harbor was found however and the expedition returned to Tasmania.

The Weddell Sea

The next summer (1841-2), Ross led the expedition back to the great ice barrier and, in spite of extensive pack ice, was able to chart further east along the ice front. In the third and final summer (1842-3), Ross hoped to penetrate the Weddell Sea and add to the research done by Weddell in 1822. They explored the eastern side of what is now known as James Ross Island, discovering and naming Snow Hill Island and Seymour Island. Unfortunately ‘dense, impenetrable, pack ice’ limited the expedition’s progress. When the expedition returned to England in September 1843, it had been away for nearly four years. Ross was awarded the Gold Medal of the Société de Géographie in 1843, elected to the Royal Society in 1848 and knighted in 1844.

Ross married Ann Coulman and settled down to private family life. Over the next five years he wrote an account of his expedition, Voyage of Discovery and Research in the Southern and Antarctic Regions During The Years 1839–43.

Later Years

Ross returned to the Arctic once more in 1848-1849. In 1845, Sir John Franklin had set out with the Erebus and Terror in search of the Northwest Passage in the Canadian Arctic. A search was mounted when he failed to return. Ross led one of many unsuccessful expeditions in search of the men.

Ross died at Aylesbury in 1862, five years after his wife. A blue plaque marks Ross’s home in Eliot Place, Blackheath, London.

————-

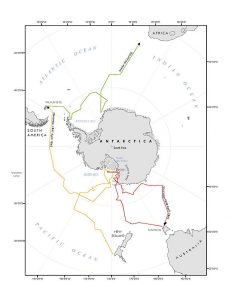

Map: Course of the Ross Expedition. Red = 1840/1. Yellow = 1841/2. Green = 1842/3. Source: Ahn Wei Lee / The Encyclopedia of Earth reproduced under Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike license.