When legendary Sir Ernest Shackleton first dreamt of crossing the miles of frozen tundra to a lonely point on the map in the early 1900s, he couldn’t have imagined the hundreds of people who would follow in his footsteps. Incredibly cold, unforgiving, relentless miles on skis to reach the South Pole does not sound pleasant to most. Yet Antarctica expeditions have been increasing in popularity, and ALE has been at the forefront of logistics, communications, and transportation necessary for safe and well-executed journeys. To provide a snapshot of all that goes into expeditions, the vocabulary, and tips for better odds at completion, we sat down with Steve Jones, our Expeditions Manager, who has worked with 75% of all people who have ever skied to the South Pole.

What are the commonly tried expedition routes in Antarctica, and any interesting variations?

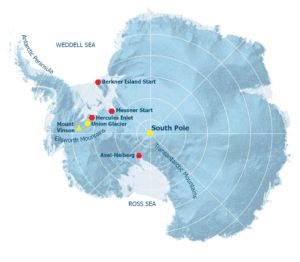

There are three popular routes from West Antarctica that one can reach by plane via our main camp, Union Glacier. The first one is Hercules Inlet. Then you have its cousin, the Messner Start, which begins further along the coast and merges with the Hercules Inlet route after the first 40%. Third is Berkner Island, which remains slightly longer, more remote, and more difficult. This isolated route has the added benefit if you want an outer coastal start rather than an inner costal start.

Other potential starting points include the bases of the glaciers through the Transantarctic Mountains such as the Axel Heiberg Glacier, traversing the same terrain that Roald Amundsen discovered more than 100 years ago. We have guided it a couple of times, but it only works as a guided expedition when we have three or four participants in one year, all of whom need to be experienced, but it remains a really exciting, challenging route. The Reedy Glacier and the Leverett Glacier are both viable options. There’s the Beardmore Glacier, very rarely travelled, the longest valley glacier on Earth and many other possible routes, some of which have been travelled, some of which have never been travelled. So there’s a lifetime of new routing through the Transantarctic Mountains. If you think of Antarctica as a pie, there’s lots of pieces of pie that nobody’s ever skied to the South Pole from. But when you look at the distances from the coast to the pole, it’s probably too far to ski in one summer season or the cost of getting to that starting point on the coast from anywhere is so high. So, although there was an interest in pioneering new routes, there are not many that have been done in recent years.

What is ALE’s history with expeditions?

Steve Jones points out key locations on a map of the Ice Marathon race course, at a race briefing

Actually this is a really interesting question because there aren’t very many routes established to the South Pole. This is because up until the 1980s, you had to get to Antarctica in your own ship, overwinter in Antarctica, and wait until spring to set off for the South Pole. So this would take years. Then ‘modern era’ if you will, began in the late 1980s with the help of air support. Adventure Network International, the precursor to ALE, had a camp at Patriot Hills, very close to ALE’s modern camp at Union Glacier. The proximity to expedition starting locations from Patriot Hills had a big influence on the development of routes. Some expeditioners chose Berkner Island as their starting location because you could theoretically get there via ship, which paid homage to the historic expeditions. Yet flying to Berkner Island required a sizeable amount of fuel, so the compromise became the current start location of Hercules Inlet, on the inner coast of the Ronne ice shelf. It was practical, more affordable, and logistically doable.

The Messner Start became a route because in 1989, ANI was supporting two significant crossing expeditions: the International Trans-Antarctic expedition with dogs, this massive international expedition never to be repeated, crossing from the top end of the peninsula out to the East Coast, and a two-man crossing by Arved Fuchs and Reinhold Messner. ANI did not have enough aviation fuel to fly Fuchs and Messner to Berkner Island, so they compromised and were dropped off on the inner coast of the Ronne ice shelf, which is near the current start named to honor Reinhold Messner.

How does one get into polar expeditions?

The best place to start now is to ask yourself the question: Can I cross-country ski? If you can’t cross country ski, go on a cross-country skiing course, workout on the skiing machine, and then go on a two-week polar training course which will be the best possible foundation in all essential skills and experience. Then you’re in a position to build experience. Depending on your end goals, if you want to do a guided ski expedition, there’s a path to gaining more mileage and experience. If you want to go on your own on an independent team or ultimately solo, then you need to commit to spending many weeks gaining polar experience on your own or beyond the guided expeditions to build the skills, resilience, and knowledge to put that all into practice in Antarctica expeditions.

In my planning timetable, I talk to most expeditioners for two to three years. But if you are a polar novice, it’s at least three years because you can’t gain the experience in one or two.

Tell me about the terminology ‘unsupported,’ ‘supported,’ and ‘unassisted’?

So these descriptors have ended up with quite a lot of meaning. All expeditions are divided into human-powered and wind-powered (snow kiting). The human-powered skiers towing their own sleds, setting off with all their supplies and not having any resupplies along the way is an unsupported expedition. You are not allowed to offload garbage along the way and there’s quite a strict list of minor rules which add up to maintaining your unsupported status. You can’t ski on established tracks; you can’t follow other people’s tracks. You’ve got to make your own way. You are meant to have a genuine wilderness pioneering experience. If you are a human-powered expedition and you have resupplies along the way then that’s a supported expedition. And if you have a fuel spill or you contaminated all your food, you need a resupply, then you would lose your unsupported status and you become a supported expedition. Unassisted used to mean you are not using wind power, but now there’s a higher level of classification that separates expeditioners into either human-powered or snow kiting.

What goes into the food/nutrition planning for expeditions, and how does someone start that process?

Ah yes, food planning. Food is an example of the level of detail that’s needed in every aspect of expedition planning. You’re making hundreds and hundreds of decisions in your outfitting, and if you get a small percentage of those decisions wrong, you will cause your expedition to go awry and potentially even fail. You’ve got to get an awful lot of decisions right. Can you imagine going to the supermarket and buying everything you’re going to eat for the next two months and then ripping off as much of the packaging as you can and putting it in a cart and saying, right, all the food I’m going to eat for the next 50 days, I have to carry around with me and can’t leave my person. I have to physically move it everywhere. I mean, it’s just a crazy thing to try and do, and that is what unsupported expeditions are doing.

It takes a lot of planning, it takes a lot of research and the people who are good at it fine-tune what they’re going to eat to their own body and their own metabolism and their individual needs. If you’re in a team, then not everybody will necessarily want the same food.

You want to take trial everything before you go, living off freeze dried meals for a few weeks at some point months beforehand, and try them on your training expeditions because your taste buds are probably slightly different when it’s minus 20. The repetitive nature of it just becomes a trial. One of my key messages is buy variety, buy stuff from different manufacturers and even if it’s not quite as quite as good. It’s really easy to underestimate the amount of carbs you need, the amount of protein you need, and we help people with information on how many grams of each type of nutrition you need per kg of your bodyweight.

What is the ideal roadmap for how someone would prepare their Antarctica expedition?

It would start with cross country skiing skills training if you’re not good at cross country skiing. Then a two-week polar expedition training course, then going away and gaining more experience on polar journeys on your own or with friends or with guides or guide companies in the northern hemisphere, Svalbard, Norway, Sweden, Greenland, those sorts of places or equivalents in North America. Then either saying that’s it, I’m going to come and join an ALE guided expedition or if you’re going to come on your own or an independent team, and have an unguided experience. We recommend teams embark on an unguided three-week polar journey – organized themselves for best learning opportunity. For soloists who have done all of that, add at least two weeks of a solo journey as well. It adds up to if you were starting out as a keen novice, that’s several years, probably three years worth of winters and springs spent gaining time on skis in a progressive training program leading up to being ready to come to Antarctica.

What does ALE do to help in the success of expeditioners?

We help in the very beginning stages of planning, the preparation, and during the expedition itself. The journey towards Antarctica with ALE starts with filling in a planning questionnaire and a skills questionnaire and that’s the start of a conversation. This happens in person, by email, and video calls over however long it takes.

Most expeditioners have got to gain experience, find sponsorship and fundraise. As we already discussed, gaining the skills and experience might take two or three years, but the fundraising might take longer. Throughout that time, myself and colleagues are available to support, provide information, answer questions on absolutely any aspect of expedition planning. We’ve got pages and pages of useful information and guides on all aspects that will add up to potentially hundreds of emails over a period of years to get to know them really well. And so we work really hard to make sure expeditions are as well prepared safe as they can be.

When they arrive in Punta Arenas for a few last days of final preparations, they will see the doctors, a travel safety manager who will give them a final briefing on the route, and then the expedition sets off and from there things are no longer in the expeditioner’s control. They can’t buy anything else, they can’t get a resupply without our help if they need one, so our job through the operations team at Union Glacier, who act as the main channel of communication, give any help and support that they need. Often times that might just be words of encouragement, but other times it can be practical support to repair and replace broken items.

What are some common errors or mishaps you’ve seen and how could someone prepare accordingly?

A fundamental issue is people getting their clothing on their legs wrong and wearing clothing that’s worked in the places they’ve done their training, which may not be as harsh or as cold or as windy as Antarctica. We’re working really hard to give people good advice about what to wear, but it’s quite difficult to persuade people sometimes that what works for them in Norway or works in Greenland isn’t exactly optimum for slightly different conditions in in Antarctica, and seeing people suffer from polar thigh injury every year is one of the things which could give me quite a degree of distress. People are coming to do the best wilderness experience of their lives and they have a self-inflicted injury from the environment because they’ve got something wrong with their clothing.

Some of the mishaps we’ve seen in recent years are navigational. People who have got really used to navigating using different grid systems and haven’t done any thinking in latitude and longitude and nautical miles perhaps aren’t as proficient as they could have been.

Another aspect that we see quite often is people who don’t bring a good enough repair kit, haven’t learnt enough about how to repair things and don’t have mission-critical spares. A really good example is that some ski bindings that break easily. For people who have

finished a lot of guided training, they haven’t had to make those decisions and fix things without help.

Lastly, the biggest problem that I think people have is they underestimate the overall difficulty of skiing 900-1,100 kilometers. People have been inspired by someone they’ve talked to, or pictures and videos, which don’t capture and convey the all-encompassing mental, physical, and psychological challenge of being in Antarctica and trying to ski such a long way over such a long period of time. And one of the trends we are seeing from this is more and more people who want to go solo rather than coming with their friends or as part of a guided team. The big differences between mountaineering and polar expeditioning, is that mountaineering has partners typically built into the sport, while polar expeditioners come into it as solely individuals. Many people would have a much happier and more successful time if they went with some friends or went on a guided expedition with us.

What is ALE’s communication during and after an expedition?

Although we are intimately involved with the planning, we’re below radar until the expedition’s gone public. We treat every expedition inquiry and plan as confidential within the company. We don’t publicize, we don’t share information about other expeditions until there’s information in the public domain.

During the expedition, the team is required to telephone us once a day on a schedule, which is usually timed to be in the evening when the skiers are safe in their tent and done skiing for the day. Then we know their campsite location and how far they’ve gone. We value hearing somebody’s voice because our comms operators gain a lot of non-verbal information from tone of voice, mood, and can hear if somebody’s really struggling. We have a have a legal and moral responsibility for their safety and most expeditions operate under our permit. Every expedition carries an ALE-owned Garmin InReach tracking unit so we can see where they are. We also monitor any blogs or social media updates that have so we’re not missing any information that they haven’t told us. A good example might be if someone has posted a photograph and you can see they have a discolored nose and frostbite injuries, but haven’t mentioned it on the daily scheduled calls. We try to close that loop and feed all that information back to the operations team at Union Glacier so they have a complete picture of health, safety, well-being, and equipment.

Any other gems of advice you would give to future expeditioners?

Expeditioners come from all around the world – it’s very much an international community. I would say a key piece that is often overlooked is knowledge of the English language. Our working language is English and expeditions have safety and health conversations which require a good proficiency in English. For expeditioners who don’t speak English, it is a good idea to use the training and preparation time to also study English.

Lastly, allow us to get to know you! How did you get into polar expeditions?

I have spent my adult life going on expeditions: mountaineering, polar expeditions, leading youth expeditions and managing expedition bases. I became an expedition leader and led expeditions all around the world for many years, and then had a parallel interest in polar expeditioning and organized polar expeditions, to the arctic and subarctic. After many years I first worked with ALE in 2004, firstly as the Vinson Base Camp manager, and guide, then as the field operations manager, and I have been the expeditions manager since 2008. I’ve worked with about 75% of people who have skied to the South Pole, which shows how many people have done it in recent years!